Historical Background

To give a sense of depth to our history of Harvington a possibly useful exercise is to speculate on our area before the Romans invaded Britain. From the onset there is a good deal of speculation here in attempting to place Harvington within a pre-Roman political context. Harvington's later political place in the area will be discussed in a subsequent section.

Celtic Period

One of the consequences that resulted from Julius Caesar's invasion of Gaul, completed in 51 BC, is that it sent shock waves not only across Gaul but also its effect on Britain. Several Belgic tribes migrated to Britain, one was the Atrebates who were a group based around the modern northern French town of Artois. After the Atrebates were defeated in Gaul Caesar appointed one of their number Commius as king, however this was not successful and he later fled to Britain with followers and established a new Atrebas kingdom in Southern England. The above may or may not be relevant depending on the origins of the Dobunni, who are relevant to us as they probably controlled this area.

Some authorities suggest that the Dobunni were another Belgic group who fled Gaul and may have been aligned with the above Atrebates, while others suggest they were connected to the powerful Catuvellauni to the east. In any case their base at Bagendon near Cirencester and it is from this base that, in the last decades of the first century BC, that the Dobunni expanded rapidly, south and west into Wiltshire and Somerset, east into Oxfordshire and, more importantly for us, northwards into northern Gloucestershire, parts of Worcestershire, Warwickshire and Herefordshire. This Dobunni expansion almost certainly engulfed the Harvington area. It may be significant that at this time the Kemerton hillfort on Bredon Hill was apparently taken by storm.24 The distribution of Dobunnic coins (staters) are helpful and have been found in Evesham, Childswickham, Dunnington, Alcester. Bidford-on-Avon, Bredon Hill, Badsey, Cleeve Prior, Welford-on=Avon, Rous Lench, Wixford and further afield.48

Between AD 33 & 43, coinage evidence, indicates the Dobunni were ruled by two kings Anted and Eisa. At their greatest expansion the new empire appears to have been divided with an east-west line based roughly on the Stroud area in mid Gloucestershire. Coinage distribution suggests that their rulers, Catti and later Corio and Comux, held sway to the south from circa AD 43 and 47 while Bodvoc ruled over the northern sector, it is the northern sector that interests us here. These kings or chieftains, possibly Anted & Eisa and certainly Bodvoc, are the first named individuals we have who most likely had influence over this area.

Dobunni coin of Bodvoc

There are a couple more, albeit scanty references to Dobunnians that come down to us: a tombstone at Templborough in South Yorkshire dedicating Dobunnian Rufilla whom Excingus, her husband, had met at Cirencester; the other is a Dobunnian called Trenus who's son Lucco was given a diplona appearing on a stone found in Pannonia, issued to him in AD 105.51

The General, Aulus Plautius, under the Roman Emperor Claudius, landed on the south coast of Britain in AD 43 and received a number of submissions from British rulers. While Aulus Plautius was in Kent, he appears to have received the submission of Bodvoc, king of the northern Dobunni and at this stage Bodvoc and his realm probably became a semi-independent or client kingdom. We do not know the effect the Roman invasion had on this area but if we are right then it would have been less dramatic and life for while may have continued as before, however we simply do not know.

In AD 47 Aulus Plautius was replaced by Publius Ostorius Scapula as Rome's second Governor of Britain. He immediately set about campaigning against the British and established a forward base at Glevum (Gloucester). The southern Dobunni resisted but it appears that the northern Dobunni did not as their capital at Bagendon when excavated didn't shew any sign of war damage. Bodvoc may have been replaced by a Roman official or more likely continued as the Dobunni's leader under the watchful eye of the governor. Nearby Cirencester was established as the administrative capital of the Dobunni circa AD 50-60 under the name Corinium Dobunnorum. Cirencester eventually became a regional capital of the Roman province of Britannia Prima and one of the largest towns in Roman Britain. Meanwhile Bagendon was abandoned and slowly disappeared from history until it was excavated by Mrs Clifford during 1954-56.24

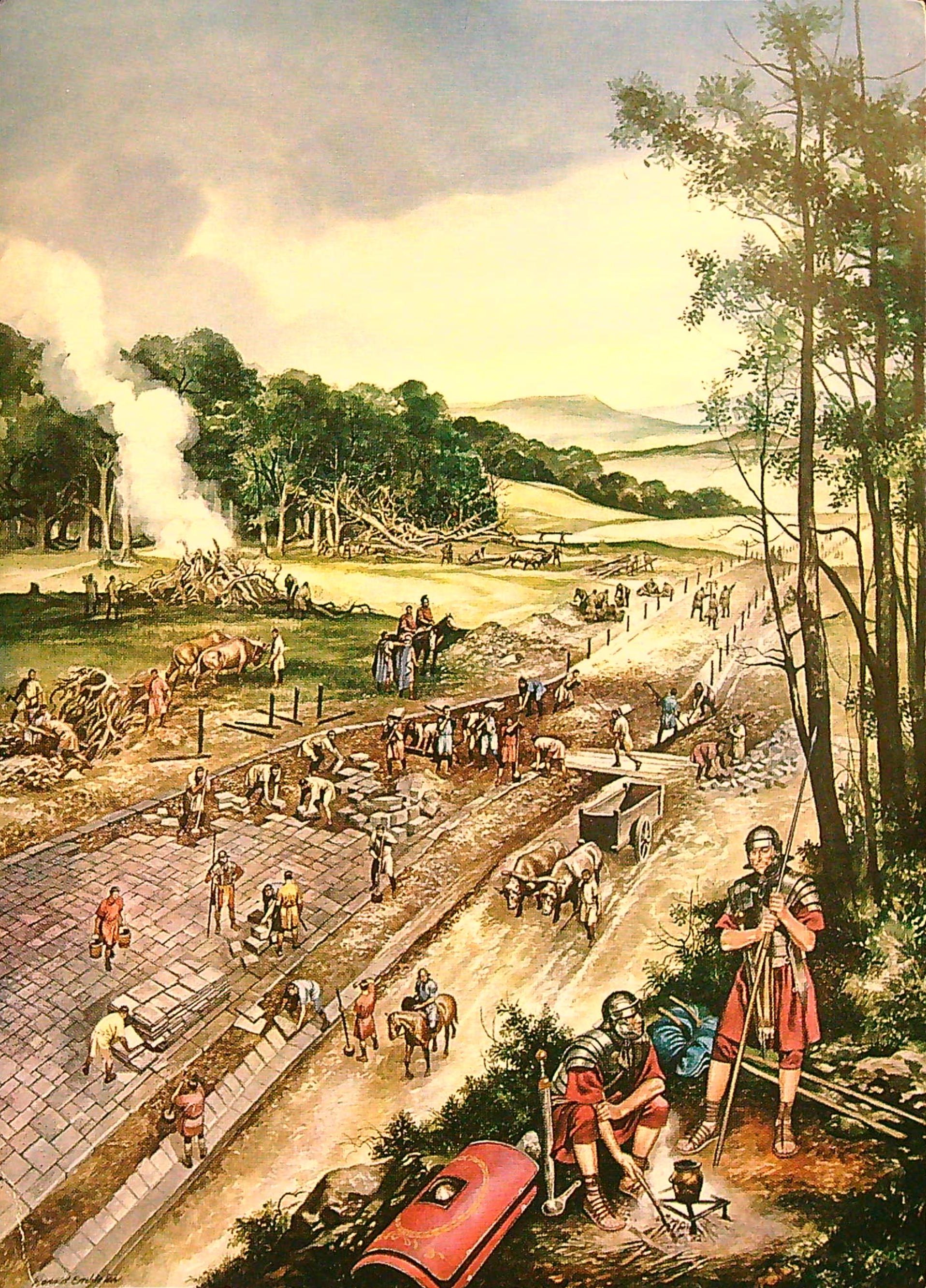

An evocative scene of the building of a Roman military road by R. Embleton.

This image was created many years ago and many miles away but imagine the road between Bidford and Honeybourne (Buckle Street), climbing towards Bickmarsh and looking west one can almost see the outline of Bredon Hill!

Roman Period

For the succeeding two hundred years Roman Britain was wealthy and stable and by the time of the Emperor Constantine by AD 314 Roman Britain was divided into four regions, which with its own political administrators and Christian bishops. The province had suffered serious barbarian attacks from the mid-3rd century onwards, which prompted the establishment of a navy (Classis Britannica), setting up of the Saxon Shore forts and the introduction of 'friendly Saxons' (federatii) and their families to help defend the country. This had been a policy on the German border for a considerable time, however in AD 367 Roman Britain suffered a concerted onslaught from all sides with raiders from Ireland and Scotland along with Franks and Saxons from the continent, which devastated the country. The wealth of the province had been concentrated in the undefended rural Roman villas and as they were wealthy they probably bore the brunt. The raiders were driven out by the Roman army under Emperor Theodosius and order was establish, but the province never fully recovered. The local effect is not known but there were estates in the area such as a probable villa at Salford Priors and certainly a number of villas across the river Avon. It was after these raids that many of the wealthier folk probably moved into the towns like Alcester for protection. Many towns were fortified at this time and probably garrisoned, again probably by friendly Franks and Saxons etc. The villa estates and countryside probably continued to be farmed as before under much the same centralized structure albeit without so much grandeur.

Governors came and went until in AD 380 Magnus Maximus was appointed governor, it is probable that it was he who reorganised the western defences, particularly in Wales where he was remembered and much loved in early Welsh literature. Whole peoples were transferred to north and mid wales to stave off attacks from Ireland. Magnus Maximus assumed the title of emperor of the Western Empire in AD 383 and apparently took parts of the Roman army from Britain to support his ambition - he was killed in AD 388. A biography of him has been written by Maxwell Craven who describes the situation in Britain in detail.51

Antona a lost Romano-British town

Returning to the local area we have a mystery - the lost town of Antona. Back in Victorian times there was talk of a lost Roman town across the River Avon in the vicinity of Aldington and Blackminster. Arthur H. Savory wrote about the town in his book Grain and Chaff and had consulted with Harvington's Rector the Revd Winnington Ingram. Both personages believed that the lost town, mentioned in Tacitus' book VII was in the Aldington/Blackminster area. There are articles on the Badsey Societys' website which deal in depth with this subject and expand on the origins of the name Aldington along with the large amount of Roman finds in the area. It is believed there was a Roman villa under Offenham and it was certainly a major estate in the 7th Century.

Romano-British Period

For historians and archaeologists there has been a sharp divide between the Roman period and that of the Anglo-Saxon depending on their expertise, separated by the so called 'Dark Ages', but now more usually 'Post Roman' period. This has now changed as our knowledge grows both in archaeology, studies of ancient charters and place names etc. Clearly some Romano-British towns and hundreds if not thousands of small settlements ceased to exist, but many continued, slowly changing over the centuries and acquiring Anglicised or English names. There have been major swings in the historian's and archaeologist's way of thinking between the English sweeping the poor defenceless British into the sea to hardly any English arriving here at all, just a few war bands. The true picture has to lie somewhere in between depending on the locality. The inexorable decline of Roman Britain in subsequent years is to be found in the last chapter of Keith Branigan's book on Roman Britain.49describes the gradual decline coupled with the survival of an independent British state.

After AD 410, a more or less unified Roman Britain continued with its own governors/kings/dictators such as figures like Ambrosius and his son Ambrosius Aurelianus and Vortigern. Much has been written about them, especially Vortigern; Ambrosius Aurelianus is mentioned by Gildas and therefore deemed a more historical figure; while Vortigern is only mentioned in early Welsh historical texts therefore his existence is deemed less reliable. Vortigern is written as local to Kent because of his dealings with Hengist and his people, Gloucester because his father Vitalis is believed to have been from there, or North Wales because that is thought to have been where he died. It is certainly possible and likely that he was an historical figure and was a ruler of Roman Britain as a whole, whether as a usurper or not.51

Vortigern is given the blame for hastening the disintegration of Roman Britain. This point is strengthened with the story that Vortigern introduced peaceful Jutes into Kent by giving them Thanet as a payment for helping to defend the eastern coast. This apparently backfired when he either refused or could not pay the new settlers, they rebelled and so started a process that eventually became unstoppable. In consequence of infighting and the mass movement of new peoples, the central authority of Roman Britain fractured into many different kingdoms fighting for supremacy over both their British neighbours and the incoming English. All this would have led to death or displacement for the ruling classes and huge disturbances and suffering for the ordinary folk, some of whom would have no doubt profited from the chaos, while others trying to keep a low profile and carry on everyday life as they knew it.49 Somewhere in this gloom there is the 'legend' of Arthur.

An interesting point made by Guy Halsall in his book Worlds of Arthur, suggests that long contact between peaceful Saxons establish here to help defend the more Romanised elements of the country may account for the number of Latin loan words in Old English.40 The British ruling class may have succumbed to a greater extent, but the ordinary folk probably continued to live out their lives, albeit gradually being absorbed and learning to speak English. Whereas as far as words from British is concerned, although many British geographical place names survive, it is to be noted that there are virtually no British (Welsh) words in English. A telling and rather chilling detail, is that while the British called themselves Cymbri, the English referred to the British as Welsh, meaning foreigner or slave. It is not often realised but Roman Britain was supported by a 'slave economy'. This was a must for the maintenance of the great villa estates and the incoming English would have been only too happy to continue with this practice. Just replace the boss and one has a ready-made income! The slave system was only abolished with the incoming of the Normans, only to be replaced by the feudal system - slavery by another name. Another element is the intermarrying between the British and English in the forging of alliances etc. The early West Saxon rulers had British names which suggests a far more complicated situation than the written history such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles describe.

During the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries many of the British kingdoms were either absorbed, evolved or replaced by English kingdoms - sometimes dramatically, sometimes by a gradual tipping of the balance from British to English. At the same time the English were also warring against each other and vying for supremacy, a dog-eat-dog scramble for dynastic land and power where many and eventually most of the early tribal groupings, war bands or small kingdoms became subordinate and then absorbed into larger kingdoms before finally disappearing, often leaving just a name for us to know they once existed, such as the Shottingas centred around Stratford upon Avon.

As far as the Harvington area is concerned a most interesting element to these rather distant events in space and time is that the area controlled by the Dobunni with their capital at Bagendon, corresponds very nicely with the later Mercian province of Hwicce. Is there a hint here of a Celtic then Roman province surviving into the post Roman British and English world? After the Romans left and any central British authority collapsed, Cirencester may have continued as a much diminished regional capital or independent post-Roman kingdom until it was conquered by the West Saxons in AD 577.

Roman and Post Roman land divisions

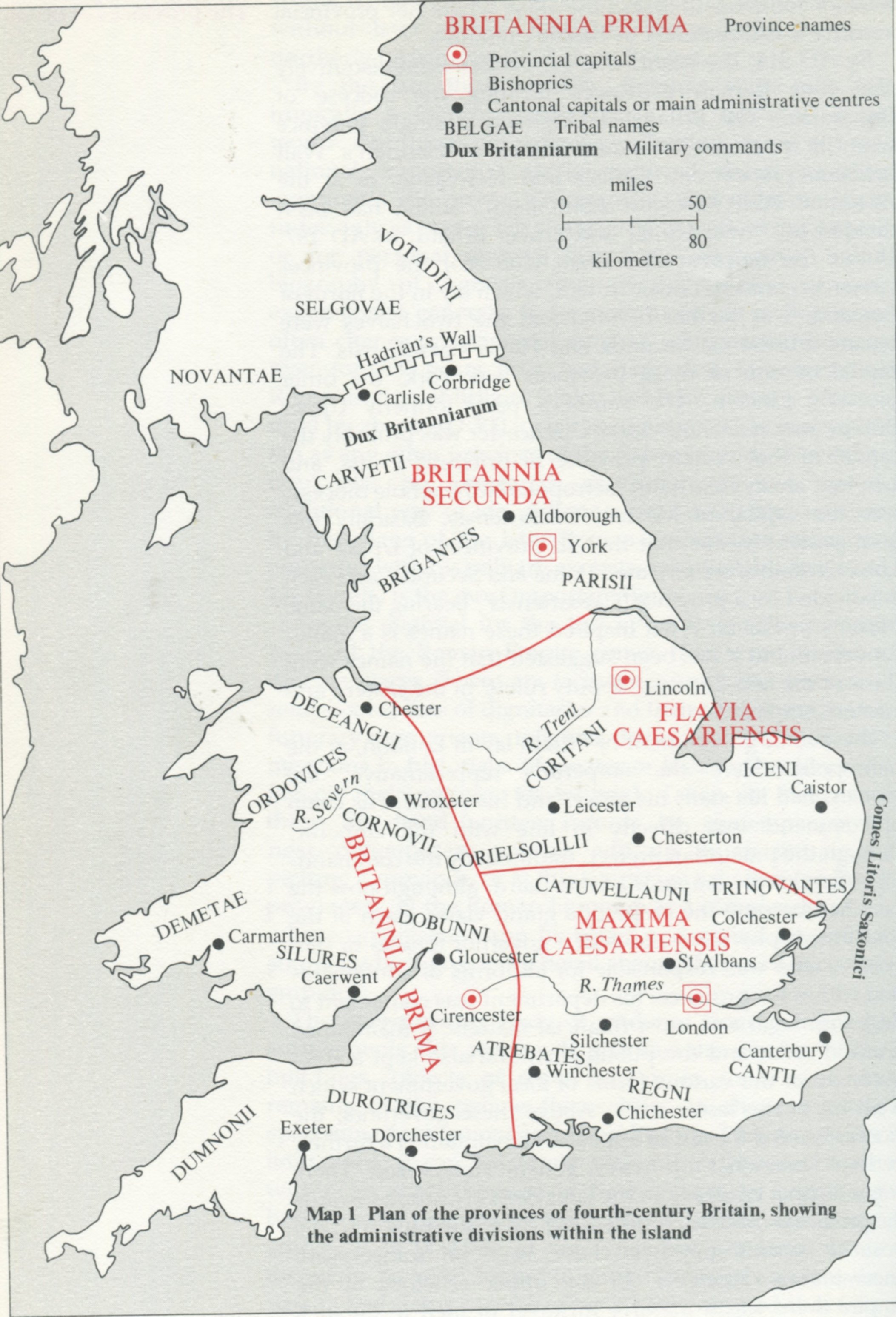

In pre-Roman times this area was possibly under the control of the Dobunni, a British tribe with their capital at Bagendon near Cirencester. Virtually no local land divisions such as estates, parishes, hundreds or counties are known from before or during the Roman period. It is likely that, at least initially, major tribes like the Dobunni, kept their smaller land divisions after the Roman conquest1. It makes more sense for the conquering power to take over an existing economy and the northern Bobunni who may have submitted to the Romans in exchange for a degree of independence and continuation. Birley in his work The Roman Government in Britain writes: "The Commonwealth (Respublica), presumably of the Dobunni, is mentioned on a fragmentary stone from their chief town Cirencester".42 Is this a faint suggestion of the existence of divisions of peoples with corresponding areas? In the late Roman period Roman-Britain was divided into four administrative regions which in themselves would have had sub-divisions, probably based on a pre-existing tribal system. We were in the administrative provence called Britannia Prima, possibly governed from Cirencester, a stone found at Cirencester records one of our governors as Lucius Septimus of the 'Remi' area in Gaul.

Administrative divisions in late Roman Britain.44

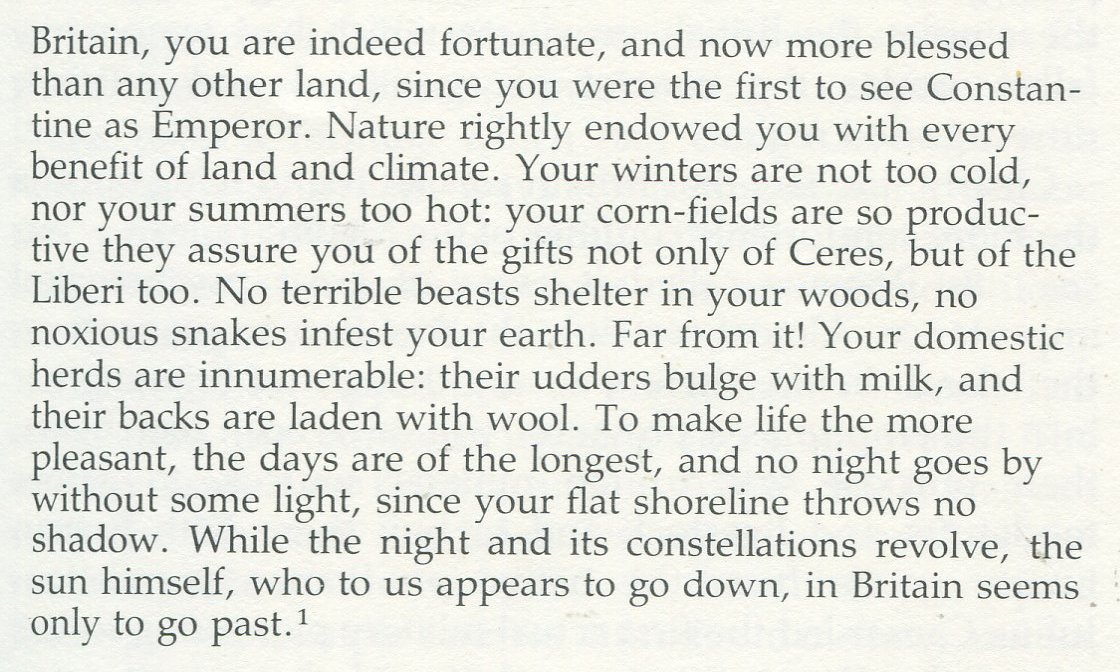

The above map shews the major late-Roman political divisions in Britain, but it does not of course tell us about the smaller administrative areas, except an indication of tribal areas of influence. The Roman land divisions were controlled from a central administrative town/city called Civitas, such as local Cirencester, Gloucester and later Alcester. Colonate/colonus/coloni is a late Roman system of territorial holdings for the folk in late Roman times, which roughly equates with and possibly a forerunner of villanage/village/villager.47. Welsh land divisions may be of help here but of course the development of the Norman feudal system has a role to play, in itself a product of late Roman and early Frankish developments. It is now gradually becoming apparent that some smaller Romano-British land divisions, such as estates, may have survived after the coming of the English and then to slowly change over time such as property boundaries do now. As a side issue, here is a very nice, if perhaps over enthusiastic, description of Roman Britain written circa AD 310.

A panegyric on Britain written in AD 310,

following the coronation of the Emporer Constantine,

from Panegyrici Latini, Mynors, Oxford 1964.